Andreas Gursky – Big Art, Big Money

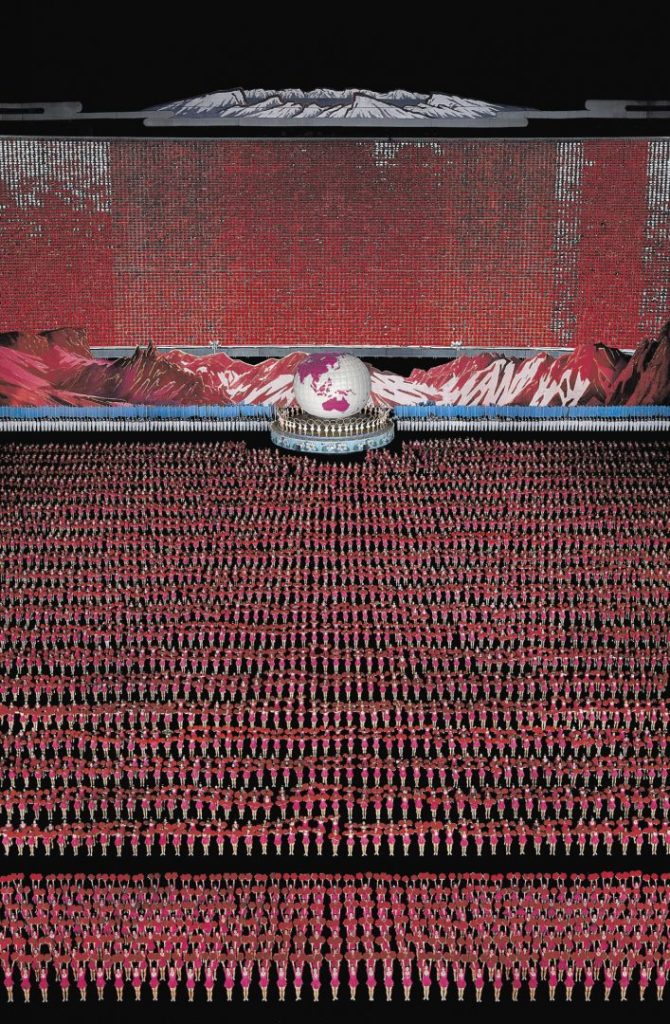

Andreas Gursky was born in 1955 and is a German photographer and professor at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Germany. He is known for his large format architecture and landscape color photographs, often employing a high point of view. Gursky shares a studio with Laurenz Berges, Thomas Ruff and Axel Hütte on the Hansaallee, in Düsseldorf. The building, a former electricity station, was transformed into an artists studio and living quarters, in 2001, by architects Herzog & de Meuron, of Tate Modern fame. In 2010-11, the architects worked again on the building, designing a gallery in the basement.

But seeing the prices his images are fetching, large scale or not, impresses even the most staid critic of photography who still questions photography’s ability to be recognized as “art”‘.

Andreas Gursky – Million Dollar Art Photography?

Gursky was born in Leipzig, former East Germany in 1955. His family relocated to West Germany, moving to Essen and then Düsseldorf by the end of 1957. From 1978 to 1981, he attended Folkwangschule, Essen, where he is said to have studied under Otto Steinert. However, it has been disputed that this can’t really be the case, as Steinert died in 1978. Between 1981-1987 at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Gursky received strong training and influence from his teachers Hilla and Bernd Becher, a photographic team known for their distinctive, dispassionate method of systematically cataloging industrial machinery and architecture. Gursky demonstrates a similarly methodical approach in his own larger-scale photography. Other notable influences are the British landscape photographer John Davies, whose highly detailed high vantage point images had a strong effect on the street level photographs Gursky was then making, and to a lesser degree the American photographer Joel Sternfeld.

While in the 1990s, Gursky did not digitally manipulate his images. In the years since, Gursky has been frank about his reliance on computers to edit and enhance his pictures, creating an art of spaces larger than the subjects photographed. Writing in The New Yorker magazine, the critic Peter Schjeldahl called these pictures “vast,” “splashy,” “entertaining,” and “literally unbelievable.” In the same publication, critic Calvin Tomkins described Gursky as one of the “two masters” of the “Düsseldorf” school. In 2001, Tomkins described the experience of confronting one of Gursky’s large works,…

Large as Large Can Be

“The first time I saw photographs by Andreas Gursky…I had the disorienting sensation that something was happening to me, I suppose, although it felt more generalized than that. Gursky’s huge, panoramic colour prints,…some of them up to six feet high by ten feet long,….had the presence, the formal power, and in several cases, the majestic aura of nineteenth-century landscape paintings, without losing any of their meticulously detailed immediacy as photographs. Their subject matter was the contemporary world, seen dispassionately and from a distance.”

The perspective in many of Gursky’s photographs is drawn from an elevated vantage point. This position enables the viewer to encounter scenes, encompassing both centre and periphery, which are ordinarily beyond reach. This sweeping perspective has been linked to an engagement with globalization. Visually, Gursky is drawn to large, anonymous, man-made spaces—high-rise facades at night, office lobbies, stock exchanges, the interiors of big box retailers (See his print 99 Cent II Diptychon).

In a 2001 retrospective, New York’s Museum of Modern Art described the artist’s work, “a sophisticated art of unembellished observation. It is thanks to the artfulness of Gursky’s fictions that we recognize his world as our own.” Gursky’s style is enigmatic and deadpan. There is little to no explanation or manipulation on the works. His photography is straightforward.

Gursky’s Dance Valley festival photograph, taken near Amsterdam in 1995, depicts attendees facing a DJ stand in a large arena, beneath strobe lighting effects. The pouring smoke resembles a human hand, holding the crowd in stasis. After completing the print, Gursky explained the only music he now listens to is the anonymous, beat-heavy style known as Trance, as its symmetry and simplicity echoes his own work—while playing towards a deeper, more visceral emotion.

99 Cent

The photograph 99 Cent (1999) was taken at a 99 Cents Only store on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, and depicts its interior as a stretched horizontal composition of parallel shelves, intersected by vertical white columns, in which the abundance of “neatly labeled packets are transformed into fields of colour, generated by endless arrays of identical products, reflecting off the shiny ceiling” (Wyatt Mason). The Rhine II (1999), depicts a stretch of the river Rhine outside Düsseldorf, immediately legible as a view of a straight stretch of water, but also as an abstract configuration of horizontal bands of colour of varying widths. In his six-part series Ocean I-VI (2009-2010), Gursky used high-definition satellite photographs which he augmented from various picture sources on the Internet.

Large Format Linhofs

Gursky shoots on 5 x 7 and 4×5 inch large-format cameras, before scanning his negatives to work on them digitally. Gursky uses 100 ASA Fuji film in two large-format Linhof cameras that are positioned side by side, one with a slight wide-angle lens, the other with a standard one. Exposure time: 1/8 of a second, f-stop 5.6 to 8. He needs this for depth of field, and the relatively low-speed film for the resolution. While any occasional blurred movement is discarded later in the process. He gains speed by underexposing the film stock one f-stop, and has it developed using push processing.

But a landscape so perfectly flat, vibrant and minimal that on first glance it appearas to be abstract now holds the record for most expensive photograph. ($4.3 Million)

The chromogenic color print, which is mounted on acrylic glass, far exceeded its sale estimate of $2.5m-$3.5m.

Rhine II, 1999, is one of an edition of six photographs by Gursky, four of which are in major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Record Prices

Hence, the previous record was set in May this year by the American artist Cindy Sherman Untitled #96 (1981), also at Christie’s in New York. The print which depicts the artist dressed up as a lovelorn adolescent, shot in 1981, fetched $3.89m.

But the late 1980s, when Gursky shot to attention, was a time when photography was first entering gallery spaces, and photographs were taking their place alongside historic paintings. However, the scale and attention to color and form in Gursky’s images can be read as a deliberate challenge to painting’s status as a “higher” art form.

But Gursky turns his lens on depersonalized, man-made or repetitious spaces – what he calls “antiseptic industrial zones”. He has famously photographed financial traders from a height, and factory workers at conveyor belts.

While the artist is frank about the fact that the hyper-real effects seen in Rhine II – the silvery water, the manicured perfection of the geometric lines and color contrasts – are a result of digitized correction. But he still uses film.

He has exhibited internationally extensively . Linhof 5×7 and Linhof 4×5

Artnet

Website