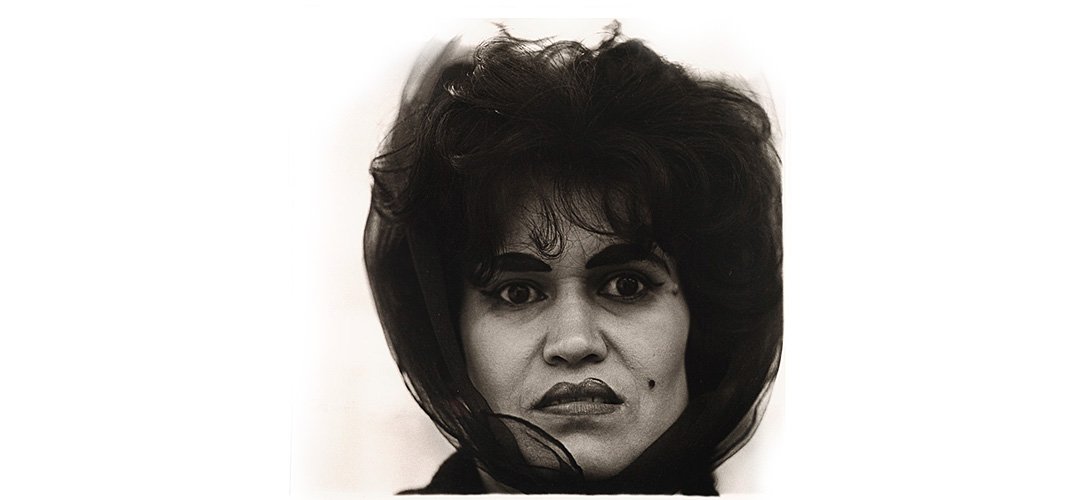

Diane Arbus

was always a pixie-child who was shy, and almost coyish, in a girlish way, in her cute little pageboy haircut. But she was anything but that. Maybe determined? Photographically obsessed? Diane grew up in a wealthy family on Central Park West in NYC.

Her first husband worked for her family in the ad department. With all the family’s NYC connections, they actually convinced those connections they were fashion photographers, and started shooting for magazines, including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and others, for nearly a decade. In a series for Glamour dubbed “Mr. and Mrs. Inc.,” they were profiled as a happy working couple. But this was another era. And playing the ‘good wife’ was expected of a woman. Demure though she was, it didn’t fit the psyche of Diane Arbus. After long hours in their studio, she’d hurry home to cook dinner for her husband and their two young daughters.

Diane Arbus – A Growing Yearning

But Diane was growing unhappy. It was she who styled all the shoots, handled the models and pinned their clothes for the shoots, while her husband, Allan, dolt that he was, felt those tasks “petty”, and beneath his station in a male dominated society. She started questioning her role, and her repressive marriage. Remember, this was way before women’s lib.

Allans’ big mistake was giving his wife her first camera and Diane started to develop an escape in photography. She didn’t want to continue working in a structured environment, but rather compose her images freely. To Allan’s dismay, it wasn’t long before she quit on the spot one day. She just wasn’t going to do it anymore. She needed to move into the world, scary or not.

She wandered the streets of New York City with her 35mm Nikon, following strangers down the street or lying in wait in doorways until she saw someone she felt compelled to photograph. This was the onset of a lifelong addiction to an experience, which would feed her and consume her in equal measure. She marked all her negatives’ glassine sleeves with a fine black marker, starting at number 1.

Numbered Negatives

Diane Arbus would continue numbering her negatives over the next 15 years, up until her suicide at the age of 48. A life experience that’s long been distorted by a cult of personality, including a movie starring Nicole Kidman as Diane Arbus. Who doesn’t look anything like Diane Arbus, and which was really nothing more than a screenwriters’ fantasy.

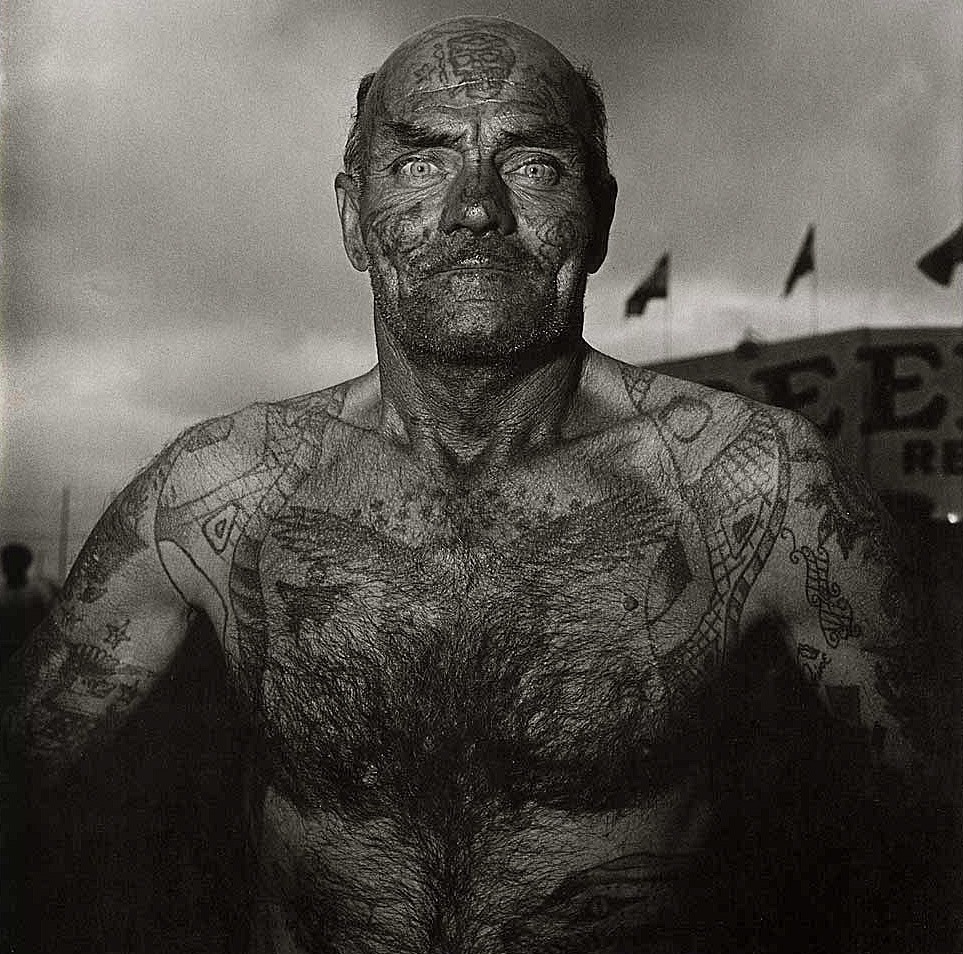

By the late ’60s, Diane was a true artist, with her striking black and white images of cross-dressers, drag performers and circus “freaks.” It was the human dimension she imbued to these people on the fringes of society. Her photos of families, children, and socialites were equally dark as she flipped the social balance. A precursor to the Gloria Steinhams sulking around the corner. With her suicide death in 1971, the galleries and museums clamored for exhibitions, making her one of the best-known photographers in history.

A Curious Life

Her legend has as much to do with the fascination with her personal life as it does with her images. Almost a photographic Frida Kahlo. However, her work was her life! She broke boundaries that were considered societal norms at the time. But she struggled with depression, being a good mother and being a photographer. She put herself in danger in getting the image she wanted many times. As an artist, competing with her male counterparts, she would do almost anything to get that image.

In her series ‘Multiples’, her photographs expose the differences that even identical twins have. As if to say, we are all unique,…having never been here before, and to never be here again.

Her birth name was Diane Nemerov, and she came from a household of talented siblings. Her brother, Howard Nemerov would eventually become a Pulitzer Prize winning poet. It was the creative life she sought from a young age, and felt that with her new husband Allan, she could build a relationship of equals. A young girls’ dream. But the reality was they were not the happiest of couples or completely monogamous, although some said they were very committed to each other.

Another World

Allan actually supported Diane, even when she quit their fashion partnership. He found her a studio and darkroom and continued his commercial work under their joint name, and developed all of her rolls of film. It was this transition from mid-century housewife to a true artist that resulted in an uncharacteristic ability to ask strangers to take off their clothes, show her their tattoos and their scars, or just how they hid their male parts under women’s panties. It was a world very far removed from Central Park West.

In the summer of 1959, Diane and Allan separated. Allan had a new girlfriend who submitted an ultimatum.Diane moved to the West Village with her girls. Even so, their lives remained close. Allan came over for Sunday brunch with his daughters, balanced their books, and processed Diane’s film.

Growing up in a 14 room mansion in NYC, her new place on Charles St. was a bit cramped, but it was completely hers. She placed a mattress on the floor and slept with her photos pinned on the walls. She cut off her hair, and became a truly androgynous working artist. Or this was how she felt. The physical transformation convinced her of her true artistry.

She became braver.She actually got closer, (physically), to her subjects. All fear seemed to have evaporated. She convinced her subjects to invite them into their homes, she cruised Times Square and the Bowery, and was fearless trying to get that image. Even decades after her death, Allan remarked that the most amazing thing about Diane was her courage.

Equipment Changed Everything

In 1962 Diane changed equipment, from a 35mm camera to a medium-format Rolleiflex. The move would define her most classic images. With larger film, the Rollei produced sharper images. And more. How she related to each subject changed. Instead of hiding behind the camera, she had to look down, focus, then looked up and started talking while simultaneously snapping the picture. This simple change of equipment enabled her to produce some of her greatest images.

A Sad End,….An Illustrious Life

Whatever empathy she felt for her subjects, Diane Arbus knew loyalty was to her work, not them. Most notoriously, there was the shoot for New York magazine at the apartment of Viva, a Andy Warhol “superstar”.Diane told her these were just head shots, but the published image bared her breasts with her head thrown back, caught in rolling her eyes in an almost sexual manner. When the issue was released, Viva threatened to sue. Founding editor Clay Felker watched advertisers run off in droves. He believed that one too-edgy image ultimately scared off about half a million dollars in revenue, and nearly sunk the magazine.

In the mid-’60s, she started photographing actual sex. She photographed couples in their beds, group-sex in the city, and swingers’ parties in clean suburban houses. She relished crossing these bounds. And in fact, she also took part. She’d found it easy enough to strip down with her New Jersey nudists, and this was just another kind of immersion to go along with the work. But her wide-open sexuality also pervaded her personal life. She slept with many of her friends, colleagues, collaborators and strangers. As far as she was concerned, she had a right to experience as much as she could. Even talk of consensual incest with her brother was skirted. By the time she was in her late 30’s, sex seemed to have become an actual compulsion.

Photography as Art

In 1967, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand were chosen as the sole three artists to be in MoMA’s first major photography shows and the exhibit, in many ways, gave credence to photography as art for the first time in history.

While Diane Arbus received much acclaim and prestige for her work during her lifetime, the financial benefits of that notoriety escaped her. She even somehow became the recipient of a reputation as someone impossible to work with. (a totally untrue art directors’ fantasy)

In Death…

A year or so after her death, MoMA decided to do a show. The MoMA show had massive crowds, and the accompanying monograph has since sold over half a million copies. Many of the prints in the exhibit would eventually sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Sadly, all after her demise and a life of struggle.

Diane Arbus’s last known negative is marked number 7459. It’s the last number we shall ever see from her. At thhe start of her career she used a Nikon F for a very short time before switching to a Rollei TLR and ended up using a Mamiya C33 TLR for many years. Find Mamiya C33

Diane Arbus on Artnet