The Beginning

Lucien Clergue was born in 1934, and died in 2014. But not before leaving the world with an indelible mark in photography that may never be repeated. It was Lucien’s mother who gave him his first camera: a Semflex TLR. (a true collectors’ item) While he eventually used a simple Rolleiflex TLR and, at the time, the newfangled Minolta SRT, he never seemed to expand beyond a Minolta X-700. His work, like his cameras, were simple and utilitarian.

“[the French Semflex was] A modest black box which triggers everything. I was thirteen years old and it was an immediate love for photography. A lifelong passion. I knew it from the first day… Right from the start, I could only envisage photography from the artistic viewpoint.” ~ Lucien Clergue

As the below is translated from French, please allow some of the English idiosyncracies

In His Own Words

People often ask me where I learned photography — at school? In books? No. With an amateur, who showed me how to frame an image, develop a film, blow up a negative. This wonderful man, with very bad eyesight and yet very skillful, had installed his laboratory in his bathroom. I installed mine in the kitchen, developing at night, the view camera serving as enlarger, set up on a lopsided packing case. Heroic times…!

Afterwards I was lent a few photography manuals. As they were most boring and diabolically resembled mathematics lessons at school, which I hated, I closed them after a few pages. And I continued to waste films, succeeding from time to time in getting a good image. Until the day when, after showing my first attempts to a friend, he told me to do a hundred more like them. I thought he was mad. I was even more so than he. I did a thousand more — and of a completely different kind!

Rules Are Made to be Broken

“You must take pictures in full sun”? I went to great pains for eight months (November 1954 – July 1955) to take them in the shade. I was fed up with all these photographic precepts: backlighting, reflections, casting shadows, play of shadows, etc. … Without flash, without lighting, using the means at hand. The artificial lighting which I used at first to make theatre portraits seemed fake to me because you can guide it by yourself. The thing that I like in natural light is the incessant variety, insomuch as we have countless problems to overcome on the spot.

The manuals advise against taking photographs in the noonday light. Recently, for almost three months, I combed through a local cemetery between twelve and one o’clock. This merciless light, hard, reflects so well the silence of necropoli. No human life, a matter between the heavens and the earth.

My peers accuse me of having a spirit of contradiction. This is to react against the déjà vu, the academic style. Do we know of a single painter amongst the top ten artists of our century who received the prize of Rome, and did not Picasso confess: “It is van Gogh who taught me just how far bad painting can go.”? Thus I cannot help but smile when, having asked me the basis of my technique, an amateur photographer exclaims: “But it’s the complete opposite of books!” I am doubtless a fool, but isn’t it photography itself which teaches us that all negative becomes positive?

By exaggerating these faults that I cultivated by ignorance of the rules, I formed, without realising it, a personal technique. An example: the developer that I use for films should be used at a temperature between 17 and 24 degrees. I heat it to 40 degrees; sometimes more. The recommended length of development is 10 to 15 minutes. In 60 or a hundred seconds I have got my result. But I monitor each film as it is being developed, which is very difficult in a closed tank.

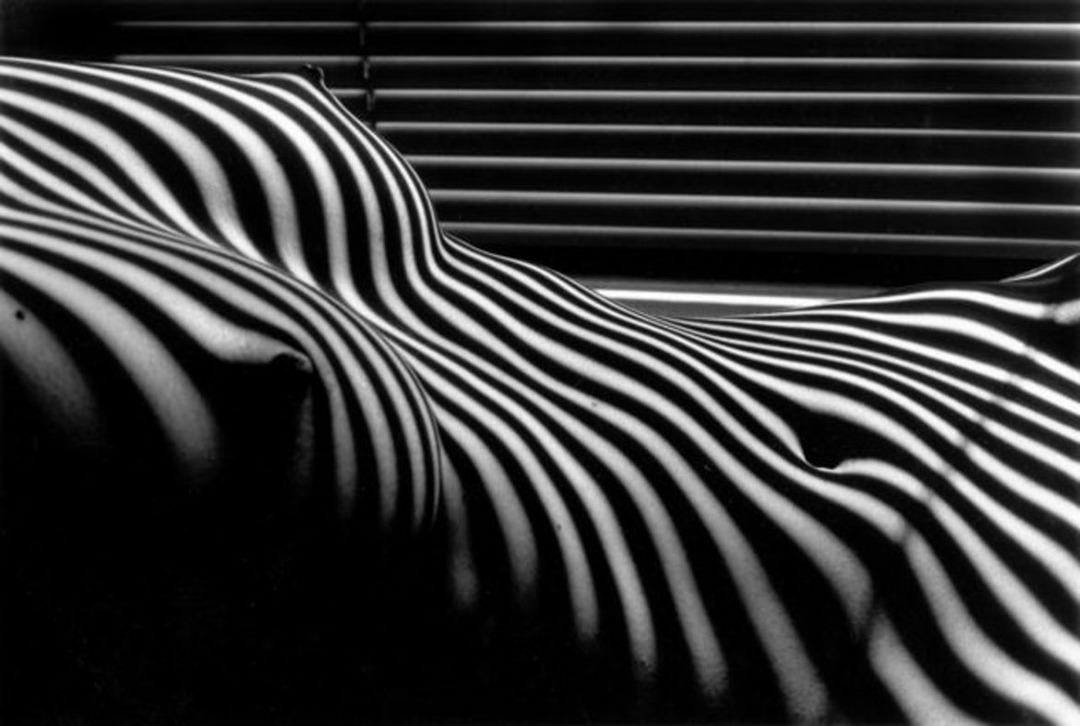

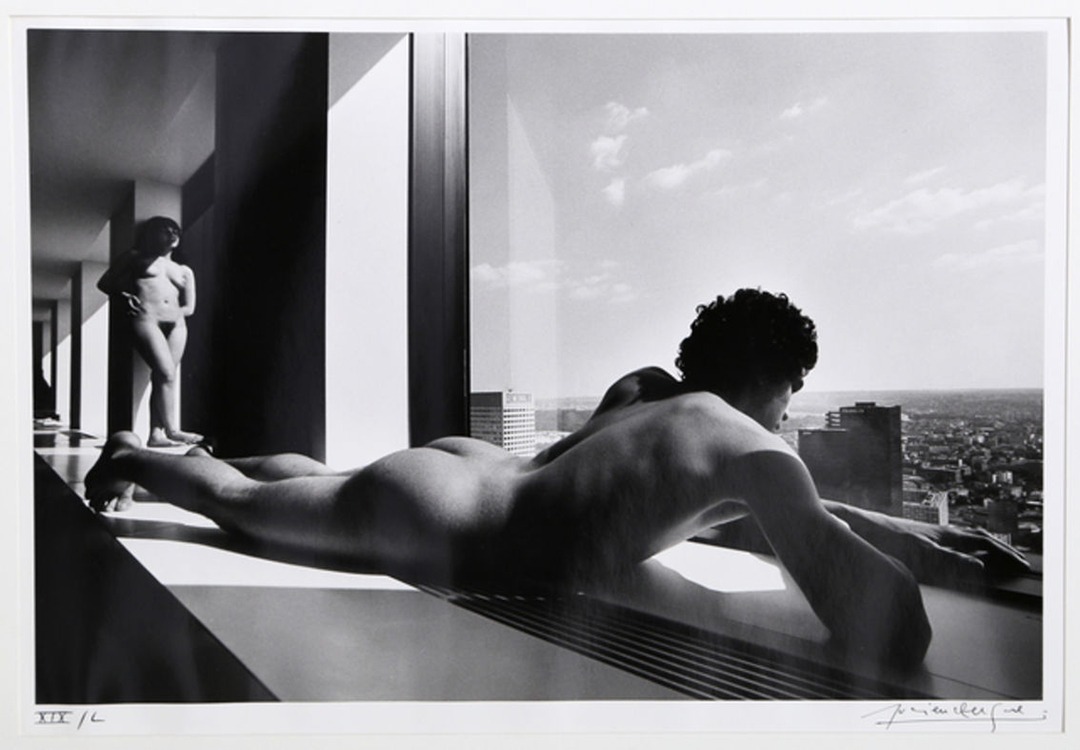

“Use yellow or orange filters for shooting at the seaside or for ancient stones.” I never use them for my nudes made at the beach and the cemetery of Montmajour was fixed without the slightest filter. It’s the reason for my white skies and certain excesses in the black and white.

A German photographer was perplexed by my explanations, and standing beside my tanks and my archaic enlarger admitted, “Photographers in my country would be pained by the sight of your atelier!” I assured him that the perfect quality of the cameras in his country prevented the soul of the artist from entering this little metal chest. We all know Brassai’s camera wrapped in elastics, or Man Ray’s unremarkable box camera. Picasso himself advised me many times to take pictures using a cardboard box, equipped with a photo sensible surface which you expose at the last minute using a pin-hole! Personally, I have stayed with a [mostly] modest French camera equipped with a 4.5 and which doesn’t exceed 1/250th of a second. What would I do working in these conditions with a lens opening at 2.8 and shutter at 1/1000th second?

Extraneous Equipment

Finally, the light meter, you say? It is indispensable for judging the luminosity of a subject? And what are eyes for, I reply? You must put the least number of intermediaries between yourself and the object being photographed. I do not like owing my images to anything but myself. By relying on this light meter, I would have the impression of only being partly responsible. If I add a filter and I print on chamois paper ‘for pretty’s sake’ I would end up being totally irresponsible. That is why I print on white glossy paper — faithful to the principles of the regretted (probably ‘revered’) Edward Weston who assures us that it is impossible to cheat with this paper — and using a single developer.

Whenever I happened to leaf through French photography magazines — apart from Photos Monde of sadly short-lived existence — it has only been to see printed there the endless formulas for developers for soft, contrasty, milky, white, dark etc. etc. … This multitude of accessories and developers is an excuse for the mediocre. How can they possibly master ten formulae when just a single one is already such a problem: too hot in summer, too cold in winter, quickly exhausted depending on the paper used; years of work have not permitted me to master this totally. I hope never to do so. I like the surprises that are in store for me.

An entire arsenal is needed to be a ‘perfect photographer’, if you go by the books. As for me, the camera slung across my chest, the supplementary close up lens and lens shield in my pocket, I try to set a trap for the invisible as Jean Cocteau so rightly says. Like any self-respecting poacher, I avoid encumbering myself with material which would only make me conspicuous to my prey or any policeman engaged in its protection.

On Developing

The first time I worked in a friend’s bathroom, having no equipment, I developed in a bowl, checking the process using a red light (at the time it was an ortho film). Since then, with panchromatic, I replaced the red with green and FP4 seems to work really well with this treatment. You have to get used to this very faint light of course, which I only switch on at the time of checking. I develop in a bath much hotter than recommended (I don’t dare say what the exact temperature is as I have never actually tested it) for about 30 to 60 seconds holding the film in both hands, which obliges me to work with rolls of 20 views. This allows me to stop the developing or on the contrary to push it. It’s a technique which would make some smile and which is very hasardous, but I like it, for after all, I don’t have to justify myself and if I make a mistake, too bad for me. It gives an extra fluttering of the heart during the mysterious sojourn in the darkroom. If the bath is too hot, then marks appear on the top of the negative where the perforations are, but the FP4 base is excellent, does not crimp and bears this shock treatment without any ill. I add some Invitol in the final rinse water and I leave to dry without heat and sheltered from dust.

On Printing

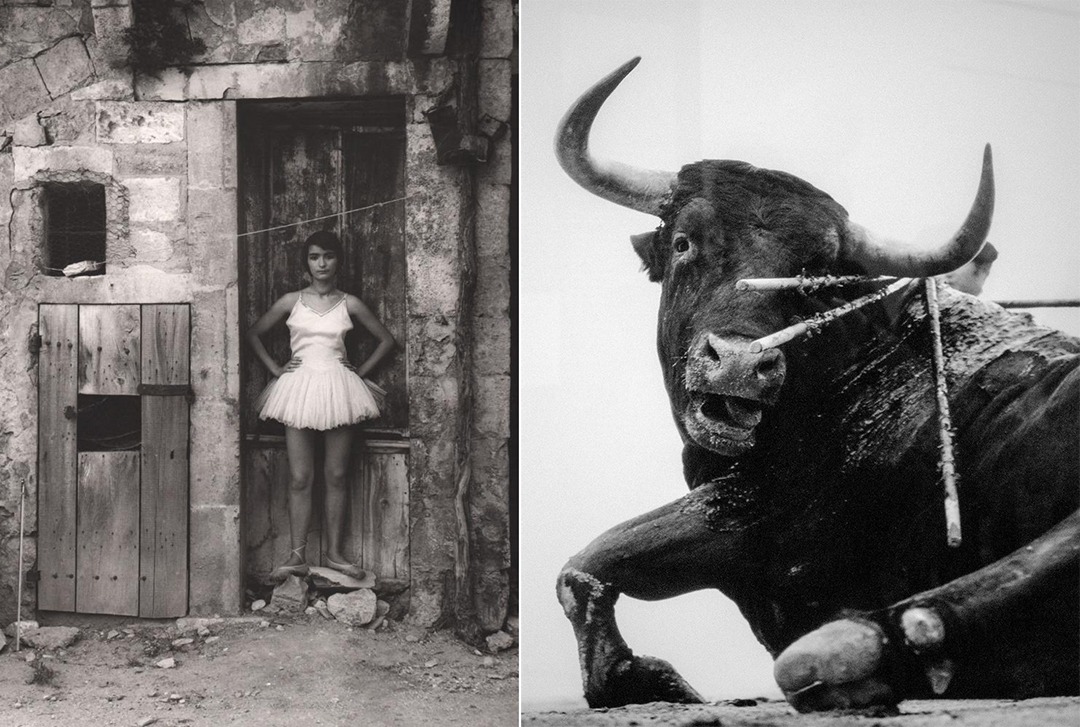

I print contact sheets very simply beneath the enlarger with the lens removed and then I let these negatives rest sometimes for months. When I make so-called working prints, I generally print 24×30 cm prints after having selected from the contact sheets. Note that for 24×36 format [35mm] I use a 55mm lens from a camera, stopped down to 5.6 and set to infinity. If a negative resists more than three attempts, I abandon it; it is obviously no good for me. I am not very patient at the enlarger and I like rapid success. Sometimes I mask parts that are too dark, but this is quite rare, although it does happen with nudes in backlighting. My paper grades are: Ilfobrom 2 for nudes and the bulls, and 2 and 3 for landscapes. The bath is at room temperature, summer as in winter and I develop right to the end, very important; rinse in an acetic acid bath; fixing for 15 to 25 minutes and a long wash, minimum one hour. Once all the working prints have been printed, I choose those that I want to enlarge to 50x60cm for exhibitions and selling to collectors.

About Glazing

As I print on 50x60cm, [20 in x 24 in] glazing is a problem. I began glazing when I was young and, through thrift, by using wardrobe mirrors. My mother was furious to see me dismantling all the wardrobes to use their doors. Later I equipped myself with mirrors obtained from the local second-hand shop.

I put some Invitol in the final rinse, next I prepare the mirror by washing it with alcohol, then I sprinkle talcum powder, which I wipe off completely with a dry cloth. All that remains is to place the print, wipe it, then press down very firmly with a double roller.

I do this in the evening and the next day the prints unstick almost unaided. When the mistral is blowing, it is quicker, when it’s humid it is slower, in winter be careful about putting them close to heaters.

Naturally, the application of this technique by just anyone would be stupid. It is important to create one’s own technique which then allows one to do it without thinking. I like to have the fewest possible intermediaries between my subject and my eyes, because then one would have the disappearance of the invisible, which has had the mad imprudence to appear. It is this ‘invisible’ which Cocteau spoke about that I try to capture in my ‘box of night’ as Michel Tournier described it, in the land where I was born, Arles and the Camargue, because though I might visit the entire world, it is always at home that I feel best.

And that is in his own words. Special thanks to his website below that provided his most eloquent words, and to Lucien Clergue himself for sharing his “deepest photographic secrets”. Something many modern photographer’s could learn from. They are not really “secrets” at all.

Website

Artnet LC Prints